Amazon Fresh Series - Part 1: Price

Low, Low Price of Market Disruption

It's easy to forget that Amazon got it’s start in 1995 by selling books on the internet. Looking back to how Jeff Bezos was able to disrupt a market that many people thought was untouchable with two brick and mortar giants in Borders and Barnes & Noble, should serve as a leading anecdote when evaluating Amazon's newest venture. As Amazon continued to undercut book prices and the two category leaders continued to ignore online as the next frontier of bookselling, the unthinkable became the inevitable. Amazon was able to draw more and more customers to utilize it's marketplace as the first stop for book shopping allowing it to slowly gobble up significant portions of individual publisher's total market share. Borders went from $1.6 Billion in profits to bankruptcy and closing 650 stores in 2011 and Barnes & Noble has been able to barely survive despite Wall Street all but writing them off. As this CNN article not so subtly recommends in it's first sentence: "Should Barnes & Noble just rename itself to Amazon's Showroom?” Amazon's category dominance has not left publisher's happy as they have continued to price under MSRP in order to gain large shares of some of the largest book publisher's sales. A little over three weeks ago, the Association of American Publishers, The Authors Guild and the American Booksellers Association sent a letter to the Chairman of the Antitrust Subcommittee referencing a 2019 New York Times article that stated "...that Amazon controlled 50% of all book distribution, but for some industry suppliers, the actual figure may be much higher, with Amazon accounting for more than 70 or 80 percent of sales." The good news throughout all of this is that for most US Grocery Stores books are almost a non-existent part of their revenue streams. Or is it?

The answer to that question may be contained in Amazon's Jeff Helbling's, VP of Amazon Fresh Stores, blog post introducing Amazon's Fresh Store in Woodland Hills, CA. It is important to note the order of the four major topics Jeff touched on in the announcement:

1.) Seamless in-store and online shopping (Convenience/Delivery)

2.) Consistently low prices (Price)

3.) Delicious food (Assortment)

4.) New ways to make grocery shopping more convenient (Dash Cart)

Emphasizing Amazon's commitment to low prices in the first half of the blog post should set off alarms for both grocers and food manufacturers across the country. There are a few items (one fresh poultry, one fresh vegetable and one national brand) that are explicitly called out with price points:

"We’ve taken our decades of operations experience to deliver consistently low prices for all, and FREE same-day delivery for Prime members. When customers visit the store, they can shop low prices across a range of national brands, quality produce, meat, and seafood. For example, Fresh brand Natural Whole Chicken with no added hormones for 99 cents/lb, a 3 lb bag of onions for $1.69, and 10 count of Quaker Oatmeal (all flavors) for $2.50."

A quick Instacart search with the Woodland Hills, CA zip code and I was able to see how these prices compared to the prices that well known Everyday Low Priced (EDLP) retailers Aldi and Walmart were advertising:

Woodland Hills, CA Price Comparison

Even though this is a small sample size, the table speaks for itself.

Platform Pricing

As this isn’t Amazon’s first brick and mortar play we should quickly review how they have approached pricing the same item in different channels. Amazon Books Store rewrote the playbook on this and didn’t even have prices on their shelf tags as you can see below.

In order to actually see what the price is of the book you had to follow the directions that were posted in a number of areas throughout the store.

Using the Amazon app on your phone, you scanned the barcode on the shelf tag that brought you to the Amazon page of the book that you were interested in. Amazon got away from not putting the price on the shelf tag for a couple of reasons. First, bookstores are built to browse. Customers tend to go to bookstores looking to get #inspired and find their next great read. It has become common practice for Publishers to print the MSRP on the book. For the most part, a paperback’s price is on the back and a hardcover’s price is either on the inside sleeve or similarly on the back of the book. Shoppers have been trained to understand that the final price of the book is the printed price. However, as you read in the introduction to this article, Amazon has gained marketshare by pricing below this price. As competitor’s tried to beat back Amazon, dynamic online pricing became necessary to have the most competitive price while not giving away too many potential sales dollars. By making the shopper check the price in the Amazon app, Amazon was able to utilize the dynamic online pricing system that they have built to combat online competitors without creating additional friction in the customer’s journey to purchase. This is because the average customer are buying 1-2 books (if they buy any at all) so an educated guess would be that shoppers in the Amazon Books store are only looking up 5-10 prices during their shopping trip. Ultimately, applying this strategy to grocery shopping would not be feasible because there are so many more items being purchased per trip and unlike physical bookstores, grocery stores always have the price points visible for the consumer at the shelf. However, it does show that Amazon has an interest in attempting to keep the offline and on-line price points the same for the consumer.

In Amazon’s introductory video for the Fresh Stores, they give us an opportunity to assess prices of their store without getting one of the coveted invitations for local shoppers.

A quick side note: checking Walmart’s Instacart price for the same item shows the same price, which add supports for our low price theory presented in Amazon’s introductory blog post.

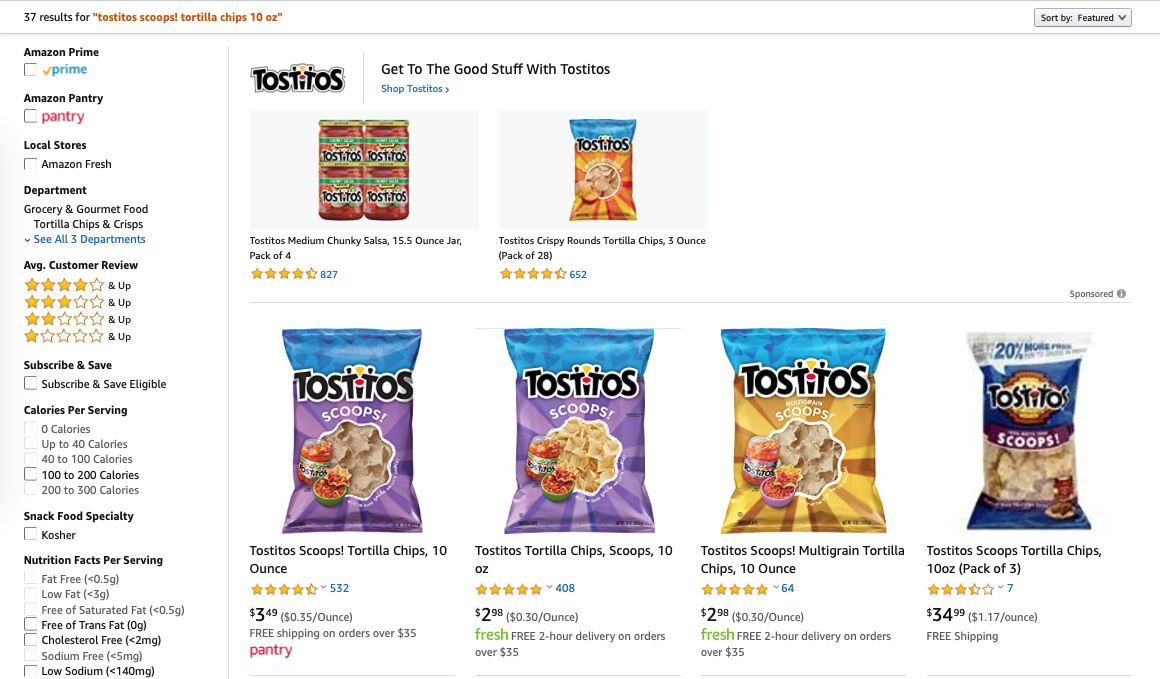

Using a screenshot of the Dash Cart, we can see a 10 oz Tostitos Scoops for $2.98 - a quick search on Amazon Fresh’s website shows the same item for the same price. Working off this and the platform pricing strategy from Amazon Books, we can with a relative degree of confidence, to assume that the prices shown on Amazon Fresh are the same as in-store. As we will see, this is just the tip of the pricing iceberg.

EPaaS: Efficient Pricing as a Service

Wait, it’s more expensive for Amazon Pantry? The Amazon Pantry service was rolled out in 2014 to allow for shoppers to buy up to 45 pounds of non-perishable household essentials in non-club size packs for an additional cost of $6 per order. Before Pantry, heavier or bulkier items required an additional cost which household club size packs regularly incurred. There is a clear reason why this item may be more expensive on the Pantry platform versus Fresh. Amazon is worried about transporting the item in a box containing up to 44 lbs and 2 ounces of other goods. Because a bag of chips has almost no structural integrity and we have all received boxes that look like this…

…the likelihood that your bag of Tostitos Scoops are transformed into a 10 ounce bag of crumbs are significantly higher than if you were to purchase them in the store or through Amazon Fresh. Amazon has most likely incurred a not-insignificant amount of write-offs because of disgruntled Amazon Pantry customers demanding to return these bags of chip shards and are using a higher price point in order to discourage people from buying this particular item through Pantry fulfillment.

In contrast, a different item that has a much lower likelihood of getting “Hulk-Smashed” en-route to your door step, Honey Nut Cheerios, tells another side of the pricing story.

In this case the Pantry delivery option is offered at a 30-40% discount compared to the Amazon Fresh fulfillment option. Amazon is now using a price discount in order to try to convince customers to use select the Pantry option. By opening stores, Amazon is making a conscious decision to take on additional human capital costs by way of cashiers, stockers and deli workers. However, by giving the customer a trade off for a lower price point for a more “planned” stock up/longer delivery window, Amazon is able to reduce the overhead costs for the items within the store and complete the order in the warehouse which they can fulfill in a more operationally efficient manner. Another added plus for getting customers to use Pantry is that Amazon is able to more effectively plan last mile logistics and give delivery drivers a higher density of deliveries distributing the outbound cost across the orders. The demand of the item remains relatively constant through this trade off but they are able to put the item through a more cost efficient distribution channel thus the ability to pass the cost savings along to the consumer. This customer transition opens the doors for them to flip the grocery game on its head.

Let’s create a simple example:

Shelf space allocation is an optimization problem that retailers constantly struggle with. How much of a certain product should I have on the shelf so that the item doesn’t need to be constantly restocked and how many items of that product can be stored in a single facing. Illustrating the example:

-Target sells 8 units of Alpo Variety Snaps (top right in the image)

-They can stock 4 products on the shelf with one facing

-If they only want to restock the item once per week, they will need two facings (like below!)

Now you can start adding variables like keeping a minimum number of items on the shelf at any given time, accounting for seasonal/holiday demand, etc. and the math required becomes more complicated. To stick with the simpler example, Amazon can aggregate the in-store and offline demand in order to get a full trade areas demand for a product.

Let’s say they sell 8 in-store and 8 online in a week. Having a cheaper online price point could shift a given week’s demand to 4 in-store and 12 online. This means that instead of needing 2 facings of the product on the shelf they can reduce it to 1, freeing up a space for another product. If this were to happen continuously all across the store, Amazon could open up a significant amount of shelf space for new products, essentially transforming their store into a pseudo hybrid retailer showroom. This type of physical retail space utilization has been recently observed in some of the larger DTC companies like Warby Parker’s entry into the physical retail space. It is less about purchasing the products at the store and more about exploring and finding new products when you are picking up your grocery order or running in to find a few last minute ingredients for your kid’s lunch. They are able to show more products in the store and offer them EDLP pricing to match the lowest priced competitors in the market in a fulfillment channel that is most cost efficient for them. Win for Amazon and win for the consumer. Understanding what new products to introduce will be discussed in more detail when we talk about Amazon Fresh’s assortment.

It’s important to caveat that Amazon has been executing personalized pricing across their platform for quite some time and so different price points may be shown to different Prime Customers but creating bounds for their optimization algorithm allows them to optimize the customer purchase decision as well as operational costs. A/B tests happen all over their website everyday with every visitor which is part of the recipe Amazon successfully executes to turn a visitor into a satisfied customer. How this optimizes the organization’s broader cost and operational efficiency is the secret sauce.

Private Label Trialing

In the blog announcement of Amazon Fresh Stores, two new private label brands were introduced to the customers. Using Private Label to cover low price points within the market is not a new strategy for retailers. This has helped retailers to avoid a poor (read: high) price perception among their consumers and reach a broader swath of the population. Amazon Private Label has gotten a bad rap because of the accusations that they are using third party sellers data in order to actively search out categories and items that are selling well on their platform and then create private label variations and offer them lower price points. This practice should not be a revelation to anyone in the grocery industry who has worked with or on private label development as many retailers have used internal sales data in order to prioritize and grow their private label assortment. Many times these private label items closely mirror the national brand in quality, ingredients and even packaging. Assuming the retailer has actually developed a good product, their main goal is to get the shopper to trial the product and decide for themselves that they are not sacrificing quality for savings of 20-30%. The shopper’s decision to put the private label mac & cheese in the basket instead of Kraft primarily hinges on two factors, packaging/marketing and price. As we have seen, Amazon is using pricing strategies for a number of different cost/operational efficiencies - Will Private Label be any different?

Happy Belly… Happy Bank Account!

Unsurprisingly, the answer is no. There is actually more to this price difference than can be first intuited. First things first, the potential to have the same write-off avoidance approach as the Tostitos shown above is very relevant. However, when we think about the consumer’s decision to buy this product instead of a Tostitos equivalent, the first thing that Amazon has established is the lowest price point. In Amazon Fresh stores they have a ‘B’ brand (lesser known National Brand - often, but not necessarily of a lower quality) that is offered at a lower price point than Tostitos. Amazon needs to get the price point below this ‘B’ brand and so this could be one explanation of the price difference. Remember that consumers, once enticed by the price savings, often do item to item comparisons in order to understand if there are any apparent differences in quality such as using cheaper or lower quality ingredients. Having a lower in-store price point removes part of the barrier to trial for the shopper and once they are convinced that they aren’t sacrificing on quality, they are likely to continue to purchase the product regardless if it is reasonably more expensive in another delivery channel because it is still the cheapest. Important to note here that the price gap is fairly significant, ~40% and so it looks like Amazon is optimizing to be the lowest price in each channel as opposed to understanding the price relationship that is shown in the resulting search for product. Understanding the price elasticity for these items in the different channels and even by Prime Member ,could easily be something Amazon could achieve allowing them to most efficiently price these products across each shopping trip.

Undoubtedly, Amazon’s hundreds, if not thousands of data scientists, machine learning engineers and AI practitioners are working on a number of the optimization problems in new and exciting ways that the retail space probably hasn’t seen or executed on before. Now, Amazon’s prices and price strategy look to omit a circular and thus the need for complicated brand negotiations involving trade dollars. This practice is common in EDLP and Discounters where the trade dollars that would’ve been deployed on promotional activity are rerouted to offset the buying price of the item for the retailer. Brands now spend on Amazon’s marketplace to get placement and banner ads in the search results but this is at their expense and should not effect the overall sourcing cost of the product. Instacart, Walmart and Kroger are a few examples of where brands are also deploying capital in this way in order to shape the customers behavior. Amazon has shown, now almost two decades ago that they are willing to sell products below cost in order to gain market share and develop the customers behavior. Will food brands, that are notorious for cracking down on this type of retailer behavior, let Amazon price below cost in order to execute on this goal. Unlike in the early 2000’s, Amazon now has a personal ATM machine in AWS that prints money for their business and allows spend a mid-size retailers yearly net sales in research & market/product development that few if any companies in the world have available. Customers showed with books that they are willing to explore new fulfillment methods and wait for their products if it meant they were saving money. If Amazon does deploy this strategy, the current economic environment and customers moving their food spend to online at a rate we have never seen before, could expedite this self-fulfilling prophecy. Maybe not in the near term, but in the long term there will be grocery versions of Borders and Barnes & Noble. Acknowledging that there will be a dramatic shift is the first step for retailers to avoid this and so the important things for retailers, brands and even consumers to understand are the concepts that Amazon is or could potentially employ and how it will shape the overall customer decision making process and ultimately grocery retail. Which is a great segue into Part 2 of this series.